9.4 Stochastic and deterministic trends

There are two different ways of modelling a linear trend. A deterministic trend is obtained using the regression model \[ y_t = \beta_0 + \beta_1 t + n_t, \] where \(n_t\) is an ARMA process. A stochastic trend is obtained using the model \[ y_t = \beta_0 + \beta_1 t + n_t, \] where \(n_t\) is an ARIMA process with \(d=1\). In that case, we can difference both sides so that \(y_t' = \beta_1 + n_t'\), where \(n_t'\) is an ARMA process. In other words, \[ y_t = y_{t-1} + \beta_1 + n_t'. \] This is very similar to a random walk with drift, but here the error term is an ARMA process rather than simply white noise.

Although these models appear quite similar (they only differ in the number of differences that need to be applied to \(n_t\)), their forecasting characteristics are quite different.

Example: International visitors to Australia

autoplot(austa) + xlab("Year") +

ylab("millions of people") +

ggtitle("Total annual international visitors to Australia")

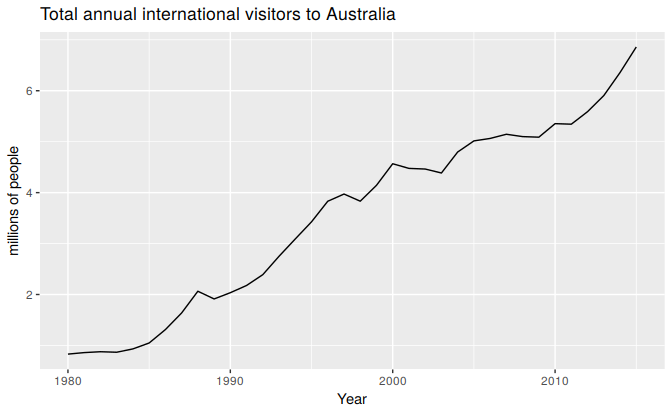

Figure 9.7: Annual international visitors to Australia, 1980–2010.

Figure 9.7 shows the total number of international visitors to Australia each year from 1980 to 2010. We will fit both a deterministic and a stochastic trend model to these data.

The deterministic trend model is obtained as follows:

trend <- seq_along(austa)

(fit1 <- auto.arima(austa, d=0, xreg=trend))

#> Series: austa

#> Regression with ARIMA(2,0,0) errors

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> ar1 ar2 intercept xreg

#> 1.11 -0.380 0.416 0.171

#> s.e. 0.16 0.158 0.190 0.009

#>

#> sigma^2 estimated as 0.0298: log likelihood=13.6

#> AIC=-17.2 AICc=-15.2 BIC=-9.28This model can be written as \[\begin{align*} y_t &= 0.42 + 0.17 t + n_t \\ n_t &= 1.11 n_{t-1} -0.38 n_{t-2} + e_t\\ e_t &\sim \text{NID}(0,0.0298). \end{align*}\]

The estimated growth in visitor numbers is 0.17 million people per year.

Alternatively, the stochastic trend model can be estimated.

(fit2 <- auto.arima(austa, d=1))

#> Series: austa

#> ARIMA(0,1,1) with drift

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> ma1 drift

#> 0.301 0.173

#> s.e. 0.165 0.039

#>

#> sigma^2 estimated as 0.0338: log likelihood=10.6

#> AIC=-15.2 AICc=-14.5 BIC=-10.6This model can be written as \(y_t-y_{t-1} = 0.17 + n'_t\), or equivalently \[\begin{align*} y_t &= y_0 + 0.17 t + n_t \\ n_t &= n_{t-1} + 0.30 e_{t-1} + e_{t}\\ e_t &\sim \text{NID}(0,0.0338). \end{align*}\]

In this case, the estimated growth in visitor numbers is also 0.17 million people per year. Although the growth estimates are similar, the prediction intervals are not, as Figure ?? shows. In particular, stochastic trends have much wider prediction intervals because the errors are non-stationary.

# fc1 <- forecast(fit1, xreg=data.frame(trend=length(austa)+1:10))

# fc2 <- forecast(fit2, h=10)

# autoplot(austa) +

# forecast::autolayer(fc2, series="Stochastic trend") +

# forecast::autolayer(fc1, series="Deterministic trend") +

# ggtitle("Forecasts from deterministic and stochastic trend models") +

# xlab("Year") + ylab("Visitors to Australia (millions)") +

# guides(colour=guide_legend(title="Forecast"))There is an implicit assumption with deterministic trends that the slope of the trend is not going to change over time. On the other hand, stochastic trends can change, and the estimated growth is only assumed to be the average growth over the historical period, not necessarily the rate of growth that will be observed into the future. Consequently, it is safer to forecast with stochastic trends, especially for longer forecast horizons, as the prediction intervals allow for greater uncertainty in future growth.