3.5 Prediction intervals

As discussed in Section 1.7, a prediction interval gives an interval within which we expect \(y_{t}\) to lie with a specified probability. For example, assuming that the forecast errors are normally distributed, a 95% prediction interval for the \(h\)-step forecast is \[ \hat{y}_{T+h|T} \pm 1.96 \hat\sigma_h, \] where \(\hat\sigma_h\) is an estimate of the standard deviation of the \(h\)-step forecast distribution.

More generally, a prediction interval can be written as \[ \hat{y}_{T+h|T} \pm k \hat\sigma_h \] where the multiplier \(k\) depends on the coverage probability. In this book we usually calculate 80% intervals and 95% intervals, although any percentage may be used. The following table gives the value of \(k\) for a range of coverage probabilities assuming normally distributed forecast errors.

| Percentage | Multiplier |

|---|---|

| 50 | 0.67 |

| 55 | 0.76 |

| 60 | 0.84 |

| 65 | 0.93 |

| 70 | 1.04 |

| 75 | 1.15 |

| 80 | 1.28 |

| 85 | 1.44 |

| 90 | 1.64 |

| 95 | 1.96 |

| 96 | 2.05 |

| 97 | 2.17 |

| 98 | 2.33 |

| 99 | 2.58 |

The value of prediction intervals is that they express the uncertainty in the forecasts. If we only produce point forecasts, there is no way of telling how accurate the forecasts are. However, if we also produce prediction intervals, then it is clear how much uncertainty is associated with each forecast. For this reason, point forecasts can be of almost no value without the accompanying prediction intervals.

One-step prediction intervals

When forecasting one step ahead, the standard deviation of the forecast distribution is almost the same as the standard deviation of the residuals. (In fact, the two standard deviations are identical if there are no parameters to be estimated, as is the case with the naïve method. For forecasting methods involving parameters to be estimated, the standard deviation of the forecast distribution is slightly larger than the residual standard deviation, although this difference is often ignored.)

For example, consider a naïve forecast for the Dow-Jones Index. The last value of the observed series is 3830, so the forecast of the next value of the DJI is 3830. The standard deviation of the residuals from the naïve method is 22.00 . Hence, a 95% prediction interval for the next value of the DJI is \[ 3830 \pm 1.96(22.00) = [3787, 3873]. \] Similarly, an 80% prediction interval is given by \[ 3830 \pm 1.28(22.00) = [3802, 3858]. \]

The value of the multiplier (1.96 or 1.28) is taken from Table 3.1.

Multi-step prediction intervals

A common feature of prediction intervals is that they increase in length as the forecast horizon increases. The further ahead we forecast, the more uncertainty is associated with the forecast, and thus the wider the prediction intervals. That is, \(\sigma_h\) usually increases with \(h\) (although there are some non-linear forecasting methods that do not have this property).

To produce a prediction interval, it is necessary to have an estimate of \(\sigma_h\). As already noted, for one-step forecasts (\(h=1\)), the residual standard deviation provides a good estimate of the forecast standard deviation \(\sigma_1\). For multi-step forecasts, a more complicated method of calculation is required. These calculations assume that the residuals are uncorrelated.

Benchmark methods

For the four benchmark methods, it is possible to mathematically derive the forecast standard deviation under the assumption of uncorrelated residuals. If \(\hat{\sigma}_h\) denotes the standard deviation of the \(h\)-step forecast distribution, and \(\hat{\sigma}\) is the residual standard deviation, then we can use the following expressions.

Mean forecasts: \(\hat\sigma_h = \hat\sigma\sqrt{1 + 1/T}\)

Naïve forecasts: \(\hat\sigma_h = \hat\sigma\sqrt{h}\)

Seasonal naïve forecasts \(\hat\sigma_h = \hat\sigma\sqrt{\lfloor (h-1)/m \rfloor + 1}\).

Drift forecasts: \(\hat\sigma_h = \hat\sigma\sqrt{h(1+h/T)}\).

Note that when \(h=1\) and \(T\) is large, these all give the same approximate value \(\hat\sigma\).

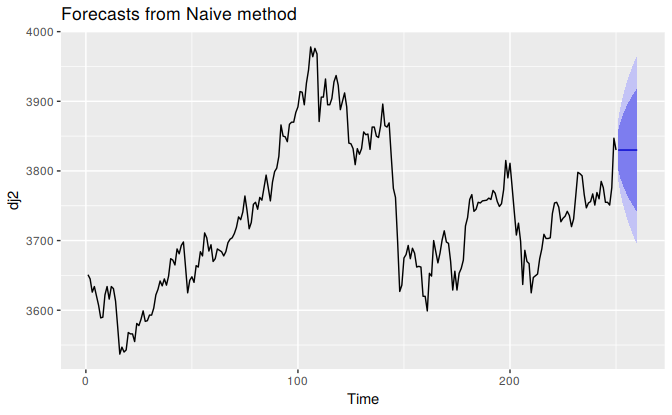

Prediction intervals will be computed for you when using any of the benchmark forecasting methods. For example, here is the output when using the naïve method for the Dow-Jones index.

naive(dj2)

#> Point Forecast Lo 80 Hi 80 Lo 95 Hi 95

#> 251 3830 3802 3858 3787 3873

#> 252 3830 3790 3870 3769 3891

#> 253 3830 3781 3879 3755 3905

#> 254 3830 3774 3886 3744 3916

#> 255 3830 3767 3893 3734 3926

#> 256 3830 3761 3899 3724 3936

#> 257 3830 3755 3905 3716 3944

#> 258 3830 3750 3910 3708 3952

#> 259 3830 3745 3915 3701 3959

#> 260 3830 3741 3919 3694 3966When plotted, the prediction intervals are shown as shaded region, with the strength of colour indicating the probability associated with the interval.

autoplot(naive(dj2))

Bootstrapped prediction intervals

When a normal distribution for the forecast errors is an unreasonable assumption, one alternative is to use bootstrapping, which only assumes that the forecast errors are uncorrelated.

A forecast error is defined as \(e_t = y_t - \hat{y}_{t|t-1}\). We can re-write this as \[ y_t = \hat{y}_{t|t-1} + e_t. \] So we can simulate the next observation of a time series using \[ y_{T+1} = \hat{y}_{T+1|T} + e_{T+1} \] where \(\hat{y}_{T+1|T}\) is the one-step forecast and \(e_{T+1}\) is the unknown future error. Assuming future errors will be similar to past errors, we can replace \(e_{T+1}\) by sampling from the collection of errors we have seen in the past (i.e., the residuals). Adding the new simulated observation to our data set, we can repeat the process to obtain \[ y_{T+2} = \hat{y}_{T+2|T+1} + e_{T+2} \] where \(e_{T+2}\) is another draw from the collection of residuals. Continuing in this way, we can simulate an entire set of future values for our time series.

Doing this repeatedly, we obtain many possible futures. Then we can compute prediction intervals by calculating percentiles for each forecast horizon. The result is called a “bootstrapped” prediction interval. The name “bootstrap” is a reference to pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps, because the process allows us to measure future uncertainty by only using the historical data.

To generate such intervals, we can simply add the bootstrap argument to our forecasting functions. For example:

naive(dj2, bootstrap=TRUE)

#> Point Forecast Lo 80 Hi 80 Lo 95 Hi 95

#> 251 3830 3803 3854 3781 3871

#> 252 3830 3790 3868 3763 3889

#> 253 3830 3782 3877 3750 3900

#> 254 3830 3775 3883 3735 3913

#> 255 3830 3768 3888 3727 3922

#> 256 3830 3761 3895 3718 3933

#> 257 3830 3753 3901 3708 3941

#> 258 3830 3749 3906 3698 3946

#> 259 3830 3746 3912 3690 3957

#> 260 3830 3740 3917 3687 3961In this case, they are very similar (but not identical) to the prediction intervals based on the normal distribution.

Prediction intervals with transformations

If a transformation has been used, then the prediction interval should be computed on the transformed scale, and the end points back-transformed to give a prediction interval on the original scale. This approach preserves the probability coverage of the prediction interval, although it will no longer be symmetric around the point forecast.

The back-transformation of prediction intervals is done automatically using the functions in the forecast package in R, provided you have used the lambda argument when computing the forecasts.