42 Fitting a linear model with neural networks

- Datasets:

Boston - Algorithms:

- Neural Networks

42.1 Introduction

https://www.r-bloggers.com/fitting-a-neural-network-in-r-neuralnet-package/

https://datascienceplus.com/fitting-neural-network-in-r/

Neural networks have always been one of the fascinating machine learning models in my opinion, not only because of the fancy backpropagation algorithm but also because of their complexity (think of deep learning with many hidden layers) and structure inspired by the brain.

Neural networks have not always been popular, partly because they were, and still are in some cases, computationally expensive and partly because they did not seem to yield better results when compared with simpler methods such as support vector machines (SVMs). Nevertheless, Neural Networks have, once again, raised attention and become popular.

Update: We published another post about Network analysis at DataScience+ Network analysis of Game of Thrones

In this post, we are going to fit a simple neural network using the neuralnet package and fit a linear model as a comparison.

42.2 The dataset

We are going to use the Boston dataset in the MASS package. The Boston dataset is a collection of data about housing values in the suburbs of Boston. Our goal is to predict the median value of owner-occupied homes (medv) using all the other continuous variables available.

dplyr::glimpse(data)

#> Rows: 506

#> Columns: 14

#> $ crim <dbl> 0.00632, 0.02731, 0.02729, 0.03237, 0.06905, 0.02985, 0.08829…

#> $ zn <dbl> 18.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 12.5, 12.5, 12.5, 12.5, 12.5, …

#> $ indus <dbl> 2.31, 7.07, 7.07, 2.18, 2.18, 2.18, 7.87, 7.87, 7.87, 7.87, 7…

#> $ chas <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0…

#> $ nox <dbl> 0.538, 0.469, 0.469, 0.458, 0.458, 0.458, 0.524, 0.524, 0.524…

#> $ rm <dbl> 6.58, 6.42, 7.18, 7.00, 7.15, 6.43, 6.01, 6.17, 5.63, 6.00, 6…

#> $ age <dbl> 65.2, 78.9, 61.1, 45.8, 54.2, 58.7, 66.6, 96.1, 100.0, 85.9, …

#> $ dis <dbl> 4.09, 4.97, 4.97, 6.06, 6.06, 6.06, 5.56, 5.95, 6.08, 6.59, 6…

#> $ rad <int> 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4…

#> $ tax <dbl> 296, 242, 242, 222, 222, 222, 311, 311, 311, 311, 311, 311, 3…

#> $ ptratio <dbl> 15.3, 17.8, 17.8, 18.7, 18.7, 18.7, 15.2, 15.2, 15.2, 15.2, 1…

#> $ black <dbl> 397, 397, 393, 395, 397, 394, 396, 397, 387, 387, 393, 397, 3…

#> $ lstat <dbl> 4.98, 9.14, 4.03, 2.94, 5.33, 5.21, 12.43, 19.15, 29.93, 17.1…

#> $ medv <dbl> 24.0, 21.6, 34.7, 33.4, 36.2, 28.7, 22.9, 27.1, 16.5, 18.9, 1…First we need to check that no data point is missing, otherwise we need to fix the dataset.

apply(data,2,function(x) sum(is.na(x)))

#> crim zn indus chas nox rm age dis rad tax

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> ptratio black lstat medv

#> 0 0 0 0There is no missing data, good. We proceed by randomly splitting the data into a train and a test set, then we fit a linear regression model and test it on the test set. Note that I am using the gml() function instead of the lm() this will become useful later when cross validating the linear model.

index <- sample(1:nrow(data),round(0.75*nrow(data)))

train <- data[index,]

test <- data[-index,]

lm.fit <- glm(medv~., data=train)

summary(lm.fit)

#>

#> Call:

#> glm(formula = medv ~ ., data = train)

#>

#> Deviance Residuals:

#> Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

#> -15.211 -2.559 -0.655 1.828 29.711

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

#> (Intercept) 31.11170 5.45981 5.70 2.5e-08 ***

#> crim -0.11137 0.03326 -3.35 0.00090 ***

#> zn 0.04263 0.01431 2.98 0.00308 **

#> indus 0.00148 0.06745 0.02 0.98247

#> chas 1.75684 0.98109 1.79 0.07417 .

#> nox -18.18485 4.47157 -4.07 5.8e-05 ***

#> rm 4.76034 0.48047 9.91 < 2e-16 ***

#> age -0.01344 0.01410 -0.95 0.34119

#> dis -1.55375 0.21893 -7.10 6.7e-12 ***

#> rad 0.28818 0.07202 4.00 7.6e-05 ***

#> tax -0.01374 0.00406 -3.38 0.00079 ***

#> ptratio -0.94755 0.14012 -6.76 5.4e-11 ***

#> black 0.00950 0.00290 3.28 0.00115 **

#> lstat -0.38890 0.05973 -6.51 2.5e-10 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> (Dispersion parameter for gaussian family taken to be 20.2)

#>

#> Null deviance: 32463.5 on 379 degrees of freedom

#> Residual deviance: 7407.1 on 366 degrees of freedom

#> AIC: 2237

#>

#> Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 2

pr.lm <- predict(lm.fit,test)

MSE.lm <- sum((pr.lm - test$medv)^2)/nrow(test)The sample(x,size) function simply outputs a vector of the specified size of randomly selected samples from the vector x. By default the sampling is without replacement: index is essentially a random vector of indeces. Since we are dealing with a regression problem, we are going to use the mean squared error (MSE) as a measure of how much our predictions are far away from the real data.

42.3 Preparing to fit the neural network

Before fitting a neural network, some preparation need to be done. Neural networks are not that easy to train and tune.

As a first step, we are going to address data pre-processing. It is good practice to normalize your data before training a neural network. I cannot emphasize enough how important this step is: depending on your dataset, avoiding normalization may lead to useless results or to a very difficult training process (most of the times the algorithm will not converge before the number of maximum iterations allowed). You can choose different methods to scale the data (z-normalization, min-max scale, etc…). I chose to use the min-max method and scale the data in the interval [0,1]. Usually scaling in the intervals [0,1] or [-1,1] tends to give better results. We therefore scale and split the data before moving on:

maxs <- apply(data, 2, max)

mins <- apply(data, 2, min)

scaled <- as.data.frame(scale(data, center = mins, scale = maxs - mins))

train_ <- scaled[index,]

test_ <- scaled[-index,]Note that scale returns a matrix that needs to be coerced into a data.frame.

42.4 Parameters

As far as I know there is no fixed rule as to how many layers and neurons to use although there are several more or less accepted rules of thumb. Usually, if at all necessary, one hidden layer is enough for a vast numbers of applications. As far as the number of neurons is concerned, it should be between the input layer size and the output layer size, usually 2/3 of the input size. At least in my brief experience testing again and again is the best solution since there is no guarantee that any of these rules will fit your model best. Since this is a toy example, we are going to use 2 hidden layers with this configuration: 13:5:3:1. The input layer has 13 inputs, the two hidden layers have 5 and 3 neurons and the output layer has, of course, a single output since we are doing regression. Let’s fit the net:

library(neuralnet)

n <- names(train_)

f <- as.formula(paste("medv ~", paste(n[!n %in% "medv"], collapse = " + ")))

nn <- neuralnet(f,data=train_,hidden=c(5,3),linear.output=T)A couple of notes:

For some reason the formula y~. is not accepted in the neuralnet() function. You need to first write the formula and then pass it as an argument in the fitting function.

The hidden argument accepts a vector with the number of neurons for each hidden layer, while the argument linear.output is used to specify whether we want to do regression linear.output=TRUE or classification linear.output=FALSE

The neuralnet package provides a nice tool to plot the model:

This is the graphical representation of the model with the weights on each connection:

plot(nn)The black lines show the connections between each layer and the weights on each connection while the blue lines show the bias term added in each step. The bias can be thought as the intercept of a linear model. The net is essentially a black box so we cannot say that much about the fitting, the weights and the model. Suffice to say that the training algorithm has converged and therefore the model is ready to be used.

42.5 Predicting medv using the neural network

Now we can try to predict the values for the test set and calculate the MSE. Remember that the net will output a normalized prediction, so we need to scale it back in order to make a meaningful comparison (or just a simple prediction).

pr.nn <- compute(nn,test_[,1:13])

pr.nn_ <- pr.nn$net.result*(max(data$medv)-min(data$medv))+min(data$medv)

test.r <- (test_$medv)*(max(data$medv)-min(data$medv))+min(data$medv)

MSE.nn <- sum((test.r - pr.nn_)^2)/nrow(test_)we then compare the two MSEs

Apparently, the net is doing a better work than the linear model at predicting medv. Once again, be careful because this result depends on the train-test split performed above. Below, after the visual plot, we are going to perform a fast cross validation in order to be more confident about the results.

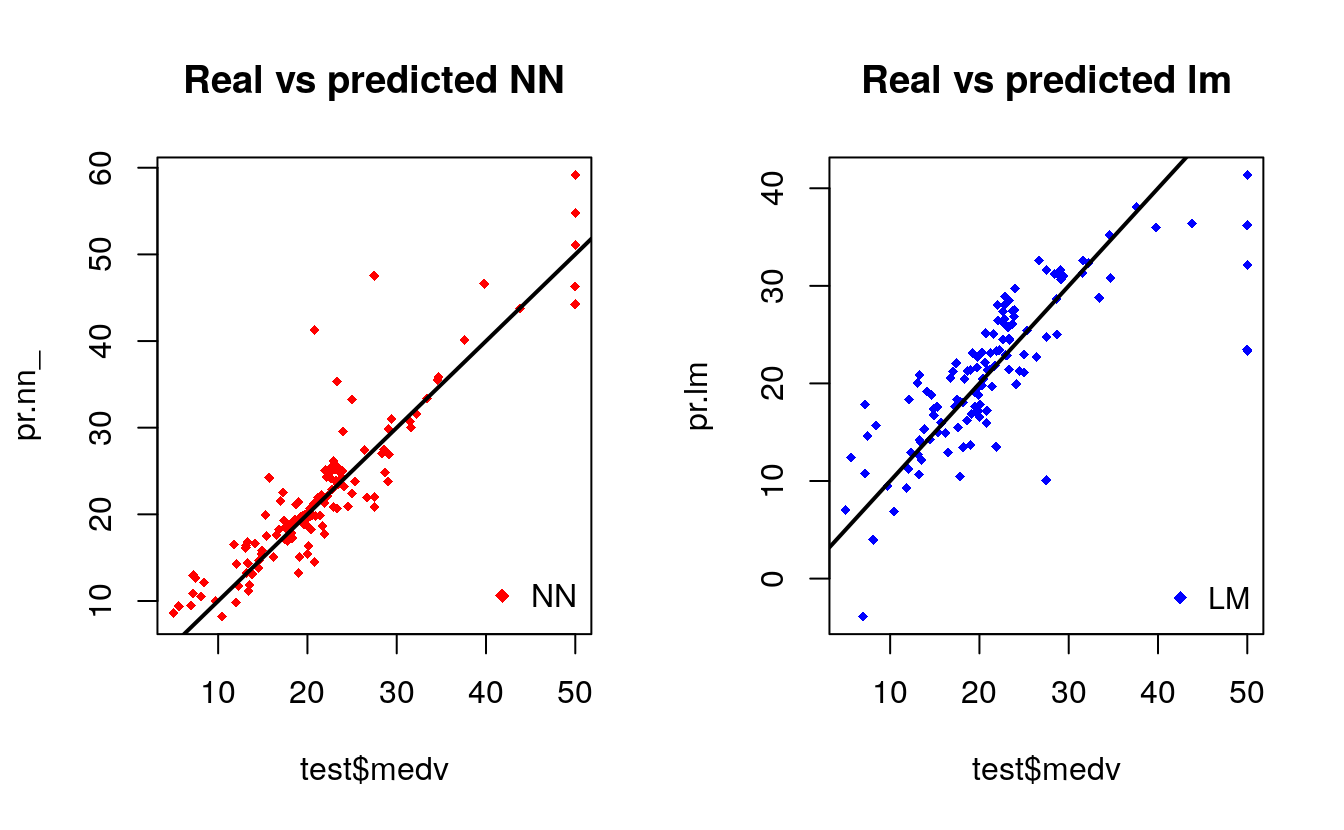

A first visual approach to the performance of the network and the linear model on the test set is plotted below

par(mfrow=c(1,2))

plot(test$medv,pr.nn_,col='red',main='Real vs predicted NN',pch=18,cex=0.7)

abline(0,1,lwd=2)

legend('bottomright',legend='NN',pch=18,col='red', bty='n')

plot(test$medv,pr.lm,col='blue',main='Real vs predicted lm',pch=18, cex=0.7)

abline(0,1,lwd=2)

legend('bottomright',legend='LM',pch=18,col='blue', bty='n', cex=.95)

By visually inspecting the plot we can see that the predictions made by the neural network are (in general) more concetrated around the line (a perfect alignment with the line would indicate a MSE of 0 and thus an ideal perfect prediction) than those made by the linear model.

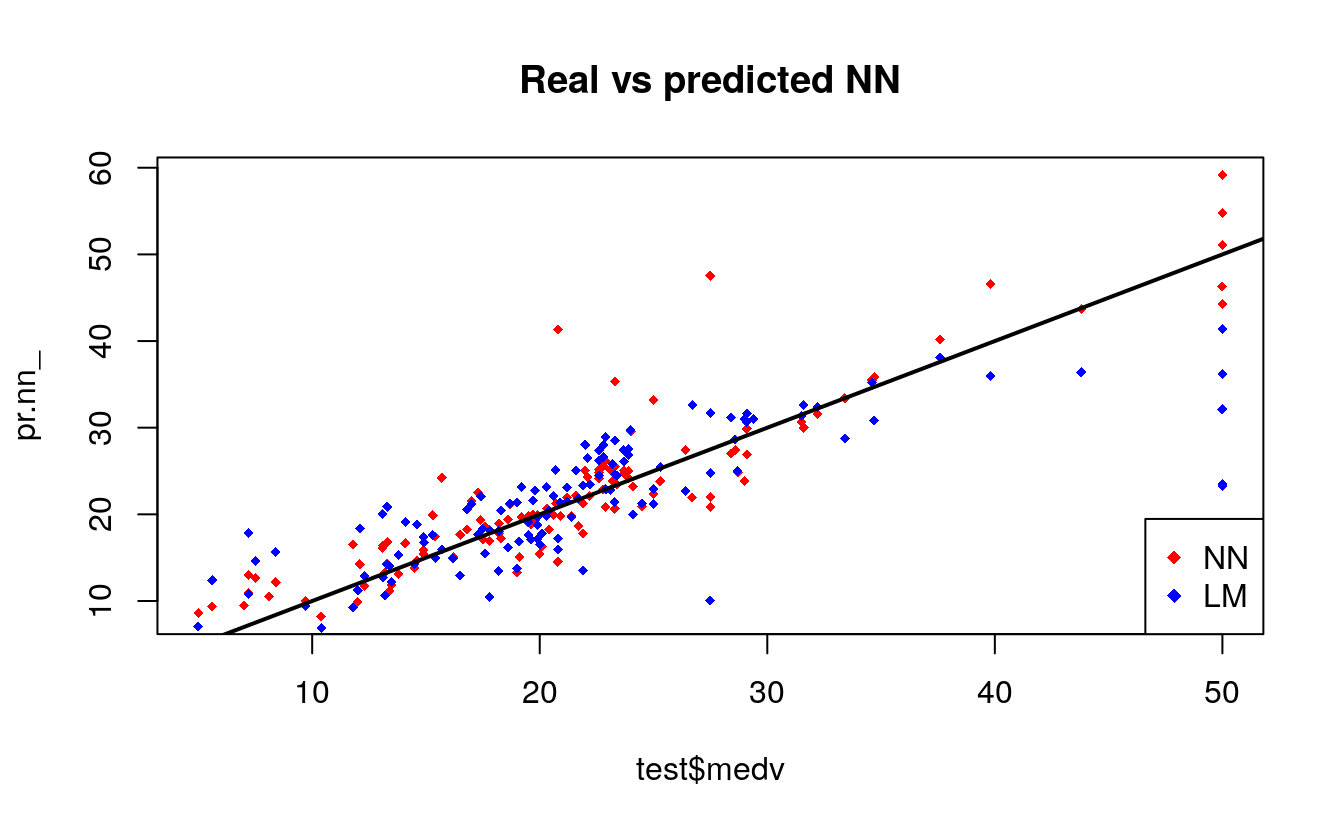

plot(test$medv,pr.nn_,col='red',main='Real vs predicted NN',pch=18,cex=0.7)

points(test$medv,pr.lm,col='blue',pch=18,cex=0.7)

abline(0,1,lwd=2)

legend('bottomright',legend=c('NN','LM'),pch=18,col=c('red','blue'))

42.6 A (fast) cross validation

Cross validation is another very important step of building predictive models. While there are different kind of cross validation methods, the basic idea is repeating the following process a number of time:

train-test split

- Do the train-test split

- Fit the model to the train set

- Test the model on the test set

- Calculate the prediction error

- Repeat the process K times

Then by calculating the average error we can get a grasp of how the model is doing.

We are going to implement a fast cross validation using a for loop for the neural network and the cv.glm() function in the boot package for the linear model. As far as I know, there is no built-in function in R to perform cross-validation on this kind of neural network, if you do know such a function, please let me know in the comments. Here is the 10 fold cross-validated MSE for the linear model:

library(boot)

set.seed(200)

lm.fit <- glm(medv~.,data=data)

cv.glm(data,lm.fit,K=10)$delta[1]

#> [1] 23.2Now the net. Note that I am splitting the data in this way: 90% train set and 10% test set in a random way for 10 times. I am also initializing a progress bar using the plyr library because I want to keep an eye on the status of the process since the fitting of the neural network may take a while.

set.seed(450)

cv.error <- NULL

k <- 10

library(plyr)

pbar <- create_progress_bar('text')

pbar$init(k)

#>

|

| | 0%

for(i in 1:k){

index <- sample(1:nrow(data),round(0.9*nrow(data)))

train.cv <- scaled[index,]

test.cv <- scaled[-index,]

nn <- neuralnet(f,data=train.cv,hidden=c(5,2),linear.output=T)

pr.nn <- compute(nn,test.cv[,1:13])

pr.nn <- pr.nn$net.result*(max(data$medv)-min(data$medv))+min(data$medv)

test.cv.r <- (test.cv$medv)*(max(data$medv)-min(data$medv))+min(data$medv)

cv.error[i] <- sum((test.cv.r - pr.nn)^2)/nrow(test.cv)

pbar$step()

}

#>

|

|======= | 10%

|

|============== | 20%

|

|===================== | 30%

|

|============================ | 40%

|

|=================================== | 50%

|

|========================================== | 60%

|

|================================================= | 70%

|

|======================================================== | 80%

|

|=============================================================== | 90%

|

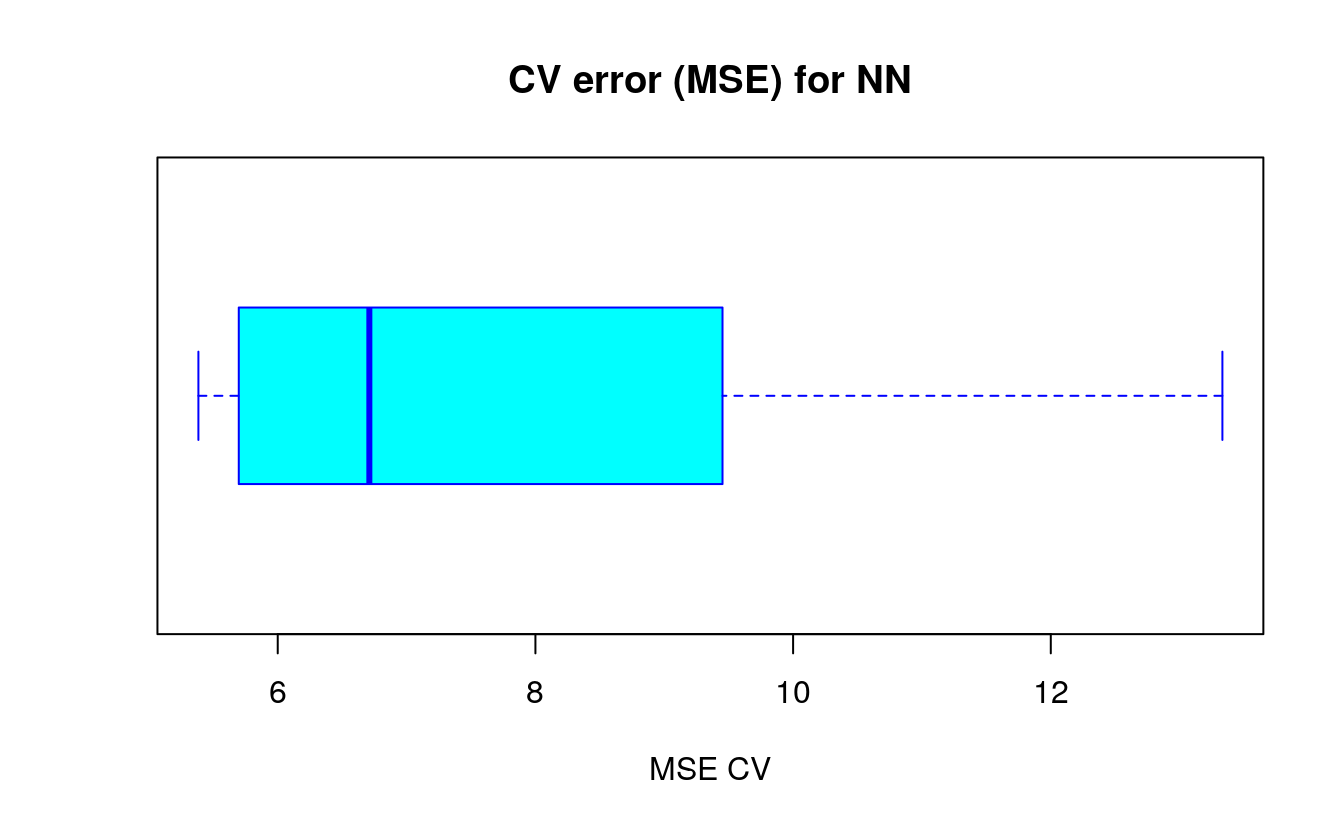

|======================================================================| 100%After a while, the process is done, we calculate the average MSE and plot the results as a boxplot

mean(cv.error)

#> [1] 7.64

cv.error

#> [1] 13.33 7.10 6.58 5.70 6.84 5.77 10.75 5.38 9.45 5.50The code for the box plot: The code above outputs the following boxplot:

boxplot(cv.error,xlab='MSE CV',col='cyan',

border='blue',names='CV error (MSE)',

main='CV error (MSE) for NN',horizontal=TRUE)

As you can see, the average MSE for the neural network (10.33) is lower than the one of the linear model although there seems to be a certain degree of variation in the MSEs of the cross validation. This may depend on the splitting of the data or the random initialization of the weights in the net. By running the simulation different times with different seeds you can get a more precise point estimate for the average MSE.

42.7 A final note on model interpretability

Neural networks resemble black boxes a lot: explaining their outcome is much more difficult than explaining the outcome of simpler model such as a linear model. Therefore, depending on the kind of application you need, you might want to take into account this factor too. Furthermore, as you have seen above, extra care is needed to fit a neural network and small changes can lead to different results.

A gist with the full code for this post can be found here.

Thank you for reading this post, leave a comment below if you have any question.